Ring of symmetric functions

In algebra and in particular in algebraic combinatorics, the ring of symmetric functions, is a specific limit of the rings of symmetric polynomials in n indeterminates, as n goes to infinity. This ring serves as universal structure in which relations between symmetric polynomials can be expressed in a way independent of the number n of indeterminates (but its elements are neither polynomials nor functions). Among other things, this ring plays an important role in the representation theory of the symmetric groups.

Contents |

Symmetric polynomials

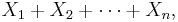

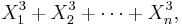

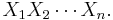

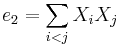

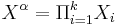

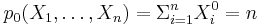

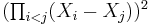

The study of symmetric functions is based on that of symmetric polynomials. In a polynomial ring in some finite set of indeterminates, there is an action by ring automorphisms of the symmetric group on (the indices of) the indeterminates (simultaneaously substituting each of them for another according to the permutation used). The invariants for this action form the subring of symmetric polynomials. If the indeterminates are X1,…,Xn, then examples of such symmetric polynomials are

and

A somewhat more complicated example is X13X2X3 +X1X23X3 +X1X2X33 +X13X2X4 +X1X23X4 +X1X2X43 +… where the summation goes on to include all products of the third power of some variable and two other variables. There are many specific kinds of symmetric polynomials, such as elementary symmetric polynomials, power sum symmetric polynomials, monomial symmetric polynomials, complete homogeneous symmetric polynomials, and Schur polynomials.

The ring of symmetric functions

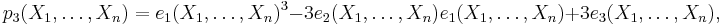

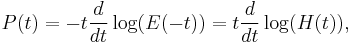

Most relations between symmetric polynomials do not depend on the number n of indeterminates, other than that some polynomials in the relation might require n to be large enough in order to be defined. For instance the Newton's identity for the third power sum polynomial leads to

where the  denote elementary symmetric polynomials; this formula is valid for all natural numbers n, and the only notable dependency on it is that ek(X1,…,Xn) = 0 whenever n < k. One would like to write this as an identity p3 = e13 − 3e2e1 + 3e3 that does not depend on n at all, and this can be done in the ring of symmetric polynomials. In that ring there are elements ek for all integers k ≥ 1, and an arbitrary element can be given by a polynomial expression in them.

denote elementary symmetric polynomials; this formula is valid for all natural numbers n, and the only notable dependency on it is that ek(X1,…,Xn) = 0 whenever n < k. One would like to write this as an identity p3 = e13 − 3e2e1 + 3e3 that does not depend on n at all, and this can be done in the ring of symmetric polynomials. In that ring there are elements ek for all integers k ≥ 1, and an arbitrary element can be given by a polynomial expression in them.

Definitions

A ring of symmetric polynomials can be defined over any commutative ring R, and will be denoted ΛR; the basic case is for R = Z. The ring ΛR is in fact a graded R-algebra. There are two main constructions for it; the first one given below can be found in (Stanley, 1999), and the second is essentially the one given in (Macdonald, 1979).

As a ring of formal power series

The easiest (though somewhat heavy) construction starts with the ring of formal power series R[[X1,X2,…]] over R in infinitely many indeterminates; one defines ΛR as its subring consisting of power series S that satisfy

- S is invariant under any permutation of the indeterminates, and

- the degrees of the monomials occurring in S are bounded.

Note that because of the second condition, power series are used here only to allow infinitely many terms of a fixed degree, rather than to sum terms of all possible degrees. Allowing this is necessary because an element that contains for instance a term X1 should also contain a term Xi for every i > 1 in order to be symmetric. Unlike the whole power series ring, the subring ΛR is graded by the total degree of monomials: due to condition 2, every element of ΛR is a finite sum of homogeneous elements of ΛR (which are themselves infinite sums of terms of equal degree). For every k ≥ 0, the element ek ∈ ΛR is defined as the formal sum of all products of k distinct indeterminates, which is clearly homogeneous of degree k.

As an algebraic limit

Another construction of ΛR takes somewhat longer to describe, but better indicates the relationship with the rings R[X1,…,Xn]Sn of symmetric polynomials in n indeterminates. For every n there is a surjective ring homomorphism ρn from the analoguous ring R[X1,…,Xn+1]Sn+1 with one more indeterminate onto R[X1,…,Xn]Sn, defined by setting the last indeterminate Xn+1 to 0. Although ρn has a non-trivial kernel, the nonzero elements of that kernel have degree at least  (they are multiples of X1X2…Xn+1). This means that the restriction of ρn to elements of degree at most n is a bijective linear map, and ρn(ek(X1,…,Xn+1)) = ek(X1,…,Xn) for all k ≤ n. The inverse of this restriction can be extended uniquely to a ring homomorphism φn from R[X1,…,Xn]Sn to R[X1,…,Xn+1]Sn+1, as follows for instance from the fundamental theorem of symmetric polynomials. Since the images φn(ek(X1,…,Xn)) = ek(X1,…,Xn+1) for k = 1,…,n are still algebraically independent over R, the homomorphism φn is injective and can be viewed as a (somewhat unusual) inclusion of rings. The ring ΛR is then the "union" (direct limit) of all these rings subject to these inclusions. Since all φn are compatible with the grading by total degree of the rings involved, ΛR obtains the structure of a graded ring.

(they are multiples of X1X2…Xn+1). This means that the restriction of ρn to elements of degree at most n is a bijective linear map, and ρn(ek(X1,…,Xn+1)) = ek(X1,…,Xn) for all k ≤ n. The inverse of this restriction can be extended uniquely to a ring homomorphism φn from R[X1,…,Xn]Sn to R[X1,…,Xn+1]Sn+1, as follows for instance from the fundamental theorem of symmetric polynomials. Since the images φn(ek(X1,…,Xn)) = ek(X1,…,Xn+1) for k = 1,…,n are still algebraically independent over R, the homomorphism φn is injective and can be viewed as a (somewhat unusual) inclusion of rings. The ring ΛR is then the "union" (direct limit) of all these rings subject to these inclusions. Since all φn are compatible with the grading by total degree of the rings involved, ΛR obtains the structure of a graded ring.

This construction differs slightly from the one in (Macdonald, 1979). That construction only uses the surjective morphisms ρn without mentioning the injective morphisms φn: it constructs the homogeneous components of ΛR separately, and equips their direct sum with a ring structure using the ρn. It is also observed that the result can be described as an inverse limit in the category of graded rings. That description however somewhat obscures an important property typical for a direct limit of injective morphisms, namely that every individual element (symmetric function) is already faithfully represented in some object used in the limit construction, here a ring R[X1,…,Xd]Sd. It suffices to take for d the degree of the symmetric function, since the part in degree d is of that ring is mapped isomorphically to rings with more indeterminates by φn for all n ≥ d. This implies that for studying relations between individual elements, there is no fundamental difference between symmetric polynomials and symmetric functions.

Defining individual symmetric functions

It should be noted that the name "symmetric function" for elements of ΛR is a misnomer: in neither construction the elements are functions, and in fact, unlike symmetric polynomials, no function of independent variables can be associated to such elements (for instance e1 would be the sum of all infinitely many variables, which is not defined unless restrictions are imposed on the variables). However the name is traditional and well established; it can be found both in (Macdonald, 1979), which says (footnote on p. 12)

The elements of Λ (unlike those of Λn) are no longer polynomials: they are formal infinite sums of monomials. We have therefore reverted to the older terminology of symmetric functions.

(here Λn denotes the ring of symmetric polynomials in n indeterminates), and also in (Stanley, 1999).

To define a symmetric function one must either indicate directly a power series as in the first construction, or give a symmetric polynomial in n indeterminates for every natural number n in a way compatible with the second construction. An expression in an unspecified number of indeterminates may do both, for instance

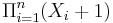

can be taken as the definition of an elementary symmetric function if the number of indeterminates is infinite, or as the definition of an elementary symmetric polynomial in any finite number of indeterminates. Symmetric polynomials for the same symmetric function should be compatible with the morphisms ρn (decreasing the number of indeterminates is obtained by setting some of them to zero, so that the coefficients of any monomial in the remaining indeterminates is unchanged), and their degree should remain bounded. (An example of a family of symmetric polynomials that fails both conditions is  ; the family

; the family  fails only the second condition.) Any symmetric polynomial in n indeterminates can be used to construct a compatible family of symmetric polynomials, using the morphisms ρi for i < n to decrease the number of indeterminates, and φi for i ≥ n to increase the number of indeterminates (which amounts to adding all monomials in new indeterminates obtained by symmetry from monomials already present).

fails only the second condition.) Any symmetric polynomial in n indeterminates can be used to construct a compatible family of symmetric polynomials, using the morphisms ρi for i < n to decrease the number of indeterminates, and φi for i ≥ n to increase the number of indeterminates (which amounts to adding all monomials in new indeterminates obtained by symmetry from monomials already present).

The following are fundamental examples of symmetric functions.

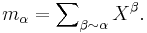

- The monomial symmetric functions mα, determined by monomial Xα (where α = (α1,α2,…) is a sequence of natural numbers); mα is the sum of all monomials obtained by symmetry from Xα. For a formal definition, consider such sequences to be infinite by appending zeroes (which does not alter the monomial), and define the relation "~" between such sequences that expresses that one is a permutation of the other; then

-

- This symmetric function corresponds to the monomial symmetric polynomial mα(X1,…,Xn) for any n large enough to have the monomial Xα. The distinct monomial symmetric functions are parametrized by the integer partitions (each mα has a unique representative monomial Xλ with the parts λi in weakly decreasing order). Since any symmetric function containing any of the monomials of some mα must contain all of them with the same coefficient, each symmetric function can be written as an R-linear combination of monomial symmetric functions, and the distinct monomial symmetric functions form a basis of ΛR as R-module.

- The elementary symmetric functions ek, for any natural number k; one has ek = mα where

. As a power series, this is the sum of all distinct products of k distinct indeterminates. This symmetric function corresponds to the elementary symmetric polynomial ek(X1,…,Xn) for any n ≥ k.

. As a power series, this is the sum of all distinct products of k distinct indeterminates. This symmetric function corresponds to the elementary symmetric polynomial ek(X1,…,Xn) for any n ≥ k. - The power sum symmetric functions pk, for any positive integer k; one has pk = m(k), the monomial symmetric function for the monomial X1k. This symmetric function corresponds to the power sum symmetric polynomial pk(X1,…,Xn) = X1k+…+Xnk for any n ≥ 1.

- The complete homogeneous symmetric functions hk, for any natural number k; hk is the sum of all monomial symmetric functions mα where α is a partition of k. As a power series, this is the sum of all monomials of degree k, which is what motivates its name. This symmetric function corresponds to the complete homogeneous symmetric polynomial hk(X1,…,Xn) for any n ≥ k.

- The Schur functions sλ for any partition λ, which corresponds to the Schur polynomial sλ(X1,…,Xn) for any n large enough to have the monomial Xλ.

There is no power sum symmetric function p0: although it is possible (and in some contexts natural) to define  as a symmetric polynomial in n variables, these values are not compatible with the morphisms ρn. The "discriminant"

as a symmetric polynomial in n variables, these values are not compatible with the morphisms ρn. The "discriminant"  is another example of an expression giving a symmetric polynomial for all n, but not defining any symmetric function. The expressions defining Schur polynomials as a quotient of alternating polynomials are somewhat similar to that for the discriminant, but the polynomials sλ(X1,…,Xn) turn out to be compatible for varying n, and therefore do define a symmetric function.

is another example of an expression giving a symmetric polynomial for all n, but not defining any symmetric function. The expressions defining Schur polynomials as a quotient of alternating polynomials are somewhat similar to that for the discriminant, but the polynomials sλ(X1,…,Xn) turn out to be compatible for varying n, and therefore do define a symmetric function.

A principle relating symmetric polynomials and symmetric functions

For any symmetric function P, the corresponding symmetric polynomials in n indeterminates for any natural number n may be designated by P(X1,…,Xn). The second definition of the ring of symmetric functions implies the following fundamental principle:

- If P and Q are symmetric functions of degree d, then one has the identity

of symmetric functions if and only one has the identity P(X1,…,Xd) = Q(X1,…,Xd) of symmetric polynomials in d indeterminates. In this case one has in fact P(X1,…,Xn) = Q(X1,…,Xn) for any number n of indeterminates.

of symmetric functions if and only one has the identity P(X1,…,Xd) = Q(X1,…,Xd) of symmetric polynomials in d indeterminates. In this case one has in fact P(X1,…,Xn) = Q(X1,…,Xn) for any number n of indeterminates.

This is because one can always reduce the number of variables by substituting zero for some variables, and one can increase the number of variables by applying the homomorphisms φn; the definition of those homomorphisms assures that φn(P(X1,…,Xn)) = P(X1,…,Xn+1) (and similarly for Q) whenever n ≥ d. See a proof of Newton's identities for an effective application of this principle.

Properties of the ring of symmetric functions

Identities

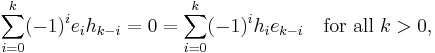

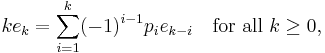

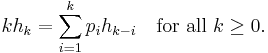

The ring of symmetric functions is a convenient tool for writing identities between symmetric polynomials that are independent of the number of indeterminates: in ΛR there is no such number, yet by the above principle any identity in ΛR automatically gives identities the rings of symmetric polynomials over R in any number of indeterminates. Some fundamental identities are

which shows a symmetry between elementary and complete homogeneous symmetric functions; these relations are explained under complete homogeneous symmetric polynomial.

the Newton identities, which also have a variant for complete homogeneous symmetric functions:

Structural properties of ΛR

Important properties of ΛR include the following.

- The set of monomial symmetric functions parametrized by partitions form a basis of ΛR as graded R-module, those parametrized by partitions of d being homogeneous of degree d; the same is true for the set of Schur functions (also parametrized by partitions).

- ΛR is isomorphic as a graded R-algebra to a polynomial ring R[Y1,Y2,…] in infinitely many variables, where Yi is given degree i for all i > 0, one isomorphism being the one that sends Yi to ei ∈ ΛR for every i.

- There is an involutary automorphism ω of ΛR that interchanges the elementary symmetric functions ei and the complete homogeneous symmetric function hi for all i. It also sends each power sum symmetric function pi to (−1)i−1 pi, and it permutes the Schur functions among each other, interchanging sλ and sλt where λt is the transpose partition of λ.

Property 2 is the essence of the fundamental theorem of symmetric polynomials. It immediately implies some other properties:

- The subring of ΛR generated by its elements of degree at most n is isomorphic to the ring of symmetric polynomials over R in n variables;

- The Hilbert–Poincaré series of ΛR is

, the generating function of the integer partitions (this also follows from property 1);

, the generating function of the integer partitions (this also follows from property 1); - For every n > 0, the R-module formed by the homogeneous part of ΛR of degree n, modulo its intersection with the subring generated by its elements of degree strictly less than n, is free of rank 1, and (the image of) en is a generator of this R-module;

- For every family of symmetric functions (fi)i>0 in which fi is homogeneous of degree i and gives a generator of the free R-module of the previous point (for all i), there is an alternative isomorphism of graded R-algebras from R[Y1,Y2,…] as above to ΛR that sends Yi to fi; in other words, the family (fi)i>0 forms a set of free polynomial generators of ΛR.

This final point applies in particular to the family (hi)i>0 of complete homogeneous symmetric functions. If R contains the field Q of rational numbers, it applies also to the family (pi)i>0 of power sum symmetric functions. This explains why the first n elements of each of these families define sets of symmetric polynomials in n variables that are free polynomial generators of that ring of symmetric polynomials.

The fact that the complete homogeneous symmetric functions form a set of free polynomial generators of ΛR already shows the existence of an automorphism ω sending the elementary symmetric functions to the complete homogeneous ones, as mentioned in property 3. The fact that ω is an involution of ΛR follows from the symmetry between elementary and complete homogeneous symmetric functions expressed by the first set of relations given above.

Generating functions

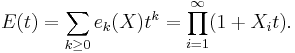

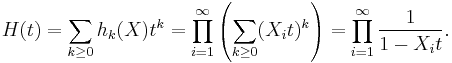

The first definition of ΛR as a subring of R[[X1,X2,…]] allows expression the generating functions of several sequences of symmetric functions to be elegantly expressed. Contrary to the relations mentioned earlier, which are internal to ΛR, these expressions involve operations taking place in R[[X1,X2,…;t]] but outside its subring ΛR[[t]], so they are meaningful only if symmetric functions are viewed as formal power series in indeterminates Xi. We shall write "(X)" after the symmetric functions to stress this interpretation.

The generating function for the elementary symmetric functions is

Similarly one has for complete homogeneous symmetric functions

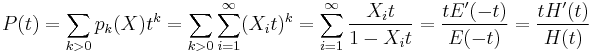

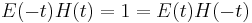

The obvious fact that  explains the symmetry between elementary and complete homogeneous symmetric functions. The generating function for the power sum symmetric functions can be expressed as

explains the symmetry between elementary and complete homogeneous symmetric functions. The generating function for the power sum symmetric functions can be expressed as

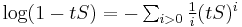

((Macdonald, 1979) defines P(t) as Σk>0 pk(X)tk−1, and its expressions therefore lack a factor t with respect to those given here). The two final expressions, involving the formal derivatives of the generating functions E(t) and H(t), imply Newton's identities and their variants for the complete homogeneous symmetric functions. These expressions are sometimes written as

which amounts to the same, but requires that R contain the rational numbers, so that the logarithm of power series with constant term 1 is defined (by  ).

).

See also

References

- Macdonald, I. G. Symmetric functions and Hall polynomials. Oxford Mathematical Monographs. The Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1979. viii+180 pp. ISBN 0-19-853530-9 MR84g:05003

- Macdonald, I. G. Symmetric functions and Hall polynomials. Second edition. Oxford Mathematical Monographs. Oxford Science Publications. The Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, New York, 1995. x+475 pp. ISBN 0-19-853489-2 MR96h:05207

- Stanley, Richard P. Enumerative Combinatorics, Vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-56069-1 (hardback) ISBN 0-521-78987-7 (paperback).